There’s one thing I’ve touched on in previous posts but not

gone into much detail on yet. Why has so much deforestation been occurring

since the 1970s? Well, there’s a number of reasons.

The first is, surprisingly, a natural cause. Natural fires,

not to be confused with anthropogenic fires, occur in forests most commonly as

a result of lightning strikes and long-term droughts. The Amazon is no

exception. In 1998, severe drought brought on by an El Niño episode burned 20,000 square kilometres of forest in the Roraima

and southeastern Pará regions of the Amazon (Nepstad et al., 2001). It seems bad, but this is natural variability in fire

occurrence, and is actually a critical component of the Earth system (Whitlock et al., 2010). Despite Amazon rainforests

being more resilient to fires due to their natural microclimates only

infrequently providing suitable conditions for fire ignition (Uhl and Kauffman, 1990; Baretto et al., 2006), anthropogenic

deforestation has been seen to increase the susceptibility of forests to fire

by providing greater ignition and fuel sources, altering the forest

microclimate to observe longer periods with no rain, and decreasing the albedo

of the land surface (Uhl and Kauffman, 1990; Nepstad et al., 2001; Silvestrini et al., 2011). The key word here: anthropogenic.

Anthropogenically-induced fires in the Amazon are common

enough that Baretto et al. (2006) defined ‘fire

zones’ in the Amazon as zones of a 10km radius around a forest fire, and

determined that 28% of the Brazilian Amazon was under significant anthropogenic

fire pressure. Fire itself is used to clear forested land for a number of uses,

referred to as ‘slash and burn agriculture’, but is just one method amongst

many, including forest clear-cutting and selective logging (Ferretti-Gallon and Busch, 2017).

A comprehensive study by Ferretti-Gallon and Busch (2017), based on 121 deforestation studies from 1996 to 2013,

found that the anthropogenic deforestation I’ve been banging on about occurs

almost exclusively due to the potential economic returns. It’s all about money

(duh!). The Amazon offers a wealth of public ecosystem services, including

biodiversity habitats, storm mitigation, and carbon storage (to name just a

few). But it seems like if the private economic returns of croplands, pasture,

mining, and urban development are greater than these ecosystem services, it’s

goodbye Amazon and hello slash and burn, but most importantly, hello money!

That’s essentially why deforestation levels I talked about in my previous post

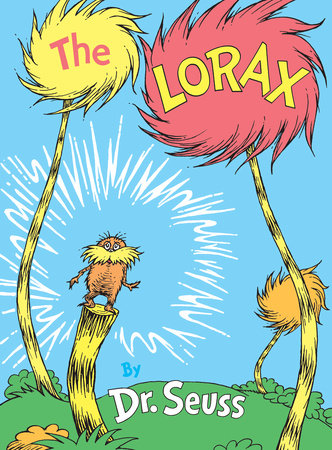

are above the optimum – it’s all about the money! Remember The Lorax?